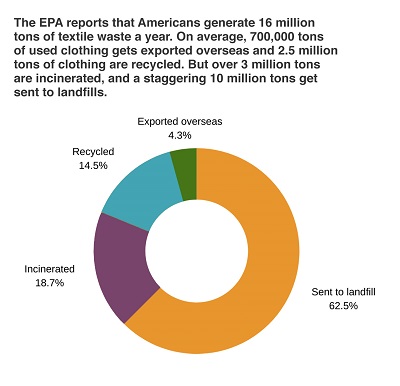

When we clean out our closets, we often use three piles for clothing: keep, donate, and toss (or, landfill). Even though many Americans donate clothes, textiles still make up a shocking amount of the US waste stream. The EPA reports that Americans generate 16 million tons of textile waste a year, equaling just over six percent of total municipal waste (for context, plastics make up 13 percent of our waste stream). On average, 700,000 tons of used clothing gets exported overseas and 2.5 million tons of clothing are recycled. But over three million tons are incinerated, and a staggering 10 million tons get sent to landfills.

We need to reduce textile waste and prevent burning or landfilling used clothing, processes that release greenhouse gas emissions. Plus, it typically costs $45 per ton to dispose of textiles, equaling hundreds of millions of dollars per year, showing a clear economic case to reduce waste.

Donating clothes can also be problematic. Bagging up and dropping off these items might end their story in our minds, but it doesn’t signify the end of life for your shirt or pair of pants. Not by a long shot.

Donate Clothing

Many people donate their worn clothing to a local charity shop. One popular charity shop chain is Goodwill, which reports that it offers many opportunities for the clothes to be resold, although roughly five percent of donated clothes are directly sent to landfills, largely due to mildew issues, which can contaminate entire bales of clothing. The rest remain in the 3,200 stores for four weeks before being moved to Goodwill outlets, found in 35 states, where items are sold for 99 cents per pound. What doesn’t sell at the outlets is then sent to Goodwill Auctions, where huge “mystery” bins full of items are sold for as little as $35 each. Finally, what clothing remains gets sent to textile recycling centers where they will be cut into rags, processed into softer fiber used for filling furniture and building insulation, or sent overseas.

Another well-known thrift store, Buffalo Exchange, operating in 19 states, purchases secondhand clothing from community members to resell in stores. It offers clothing that it cannot purchase as donations to local non-profits. Store merchandise that doesn’t sell is sent to outlet stores in Texas and Arizona. Unfortunately, most thrift stores don’t track where their donations head after they pass them along to the next step, and that includes Goodwill and Buffalo Exchange.

Textile Recycling

Recycling textiles can keep materials out of landfills and incinerators as well as reduce need for virgin fibers by extending the life of existing ones. Textiles are sorted by material type and color. Sorting by color means that no re-dying would need to take place, which saves energy and dyes. The textiles are then shredded. Zippers and buttons are removed from the shredded piles using magnets. Natural textiles, like cotton or wool, are cleaned and mixed through “carding,” a mechanical process that passes fibers between moving surfaces to break up locked clumps of fiber and aligns individual fibers to be parallel to each other. The product is then re-spun into yards of threads and ready to be used for weaving or knitting into new products.

Synthetic fibers, such as polyester or acrylic, are processed into polyester chips, which are essentially plastic pellets that become polyester again. The chips are melted and spun into new filament fiber for new polyester fabrics. There are small businesses and major brands committed to using recycled materials in their goods. For example, Patagonia sells clothing made with recycled down, wool, and polyester. Even the labels and zippers in these items contain up to 80 percent reclaimed material. Green Business Network member Ooloop uses recycled wool, cashmere, cotton, and even recycled fishing nets in its clothing. Ooloop also uses surplus material (the discards from the fashion industry), for its clothing lines to keep those materials out of landfills.

Overseas Exports

Secondhand clothes that don’t sell in the US or go into textile recycling are often exported. Roughly 700,000 tons of used clothing gets sent to other countries annually, reportedly creating a big market and contributing to job growth. But it’s highly contested whether the impacts of this trade on local economies yields beneficial or harmful results. The sheer volume of exported clothing has suppressed local clothing industries and developed an increased reliance on other countries. It’s estimated the cost of a secondhand garment is as low as five percent the cost of a new garment made in Kenya, meaning local industries are unable to compete with the influx of cheap, used clothing.

In 2016, the East African Community (EAC) agreed to a complete ban on imported clothing that would have gone fully in effect in 2019. The Trump administration pressured leaders to rescind the ban, which they eventually did. But a range of projected outcomes were debated during the multi-year discussion of the ban. Kenya had said it wouldn’t be able to follow the ban’s deadline, as it lacks the capacity to meet domestic demand for clothing and the export demand for its textiles. Local small businesses need to expand and scale up to satisfy demand. Kenya’s new garment industry had half a million garment workers a few decades ago but now only has tens of thousands.

Opponents of the ban pushed back by saying it violated international trade agreements, could have eliminated hundreds of thousands of jobs, and reduced millions of dollars of income. Donated clothing was previously given away for free in East Africa. It then became a commodity to sell, which is what suppressed the local textile sector, but created livelihoods in the secondary clothing market at the same time. In the future, the US government could work with East African nations to support the development of local textile industries while reducing the flow of garments from our secondary market.

Reduce, Reuse, and then Recycle

With almost two-thirds of clothing castoffs headed directly to the landfill, what’s abundantly clear is that we produce far too much clothing in the first place. With the influence of fast fashion, we now see over 50 “micro-seasons” of clothing being made in a year instead of the previous two seasons (spring/summer and fall/winter) from decades past.

Here are three steps you can take to reduce your impact on the Earth when it comes to clothes:

1. Reduce clothing purchases and consider the larger waste trail behind the textiles we buy. Donating clothing is far better than landfilling, but it does not erase the impacts of the clothes we buy and discard.

2. When buying clothes, choose secondhand. You can find used clothing for sale in local thrift stores or online.

3. For new items, look for “recycled content” products to ensure we are creating demand for recycled textiles, which leads to more incentive for companies to close the loop and give new life to used textiles.

Beyond these individual habits, we can advocate for less waste throughout the fashion system. Host a clothing swap to build community and show others the importance of reducing waste. Use social media and email to contact clothing companies and express the importance of designing for a loop instead of a landfill. Ask your local government to explore better collection systems for used textiles to ensure they are repurposed or recycled. Spread the word about the harm and waste perpetrated by the unsustainable fast fashion industry. For all of us who wear clothes, there are many ways we can make a difference for people and the planet.