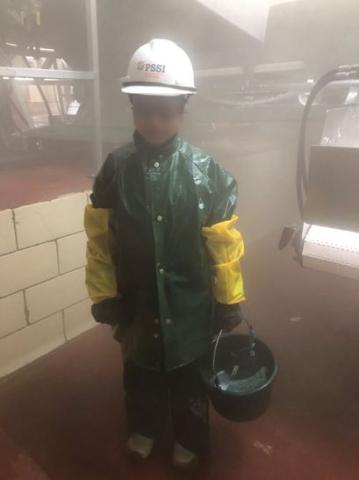

Don’t think child labor in the US is a thing of the past. In 2022, the US Department of Labor (DOL) discovered over 100 children, aged 13-17, employed in dangerous jobs at meatpacking plants across the country by Packers Sanitation Services Incorporated (PSSI).

“This isn’t kids working at Dairy Queen for too many hours, it’s kids working in meat factories, ankle deep in blood and cleaning saws,” explains Reid Maki, director of child labor advocacy at the National Consumers League (NCL) and coordinator of the Child Labor Coalition.

The DOL reported at least three children suffered chemical burns from the caustic cleaning supplies they used. Many worked night shifts after attending school all day.

“It harkens back to a Dickensian idea of child labor,” Maki says.

Though horrifying accounts of dangerous child labor conditions may seem out of place in the 21st century United States, child labor has always been present, if hidden. Exploiting children for labor has followed the familiar thread of targeting the most vulnerable, from enslaved African children on plantations to immigrant children and families experiencing severe poverty.

In 1938, advocates for children won a victory when the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) placed limitations on child labor, like prohibiting children under 16 from working in manufacturing or mining. Later amendments introduced more restrictions, but child labor has nonetheless persisted—in 2023, the DOL found a 69% increase in illegal child employment since 2018, with over 3,800 children employed illegally, likely a significant undercount. The Child Labor Coalition estimates more than 300,000 migrant children work in agriculture alone.

States Are Racing to the Bottom

Less than a year after the PSSI investigation, Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed into law a bill loosening child labor restrictions, by removing parental consent and age verification requirements. In the past two years, 10 states introduced or passed legislation rolling back protections for child laborers.

“Most of these bills are put forward by conservative legislators who believe in untrammeled parental rights [like allowing their children to work],” Maki says. Other legislation that claims to be about “parents’ rights” attack books in school libraries, LGBTQ+ content and speech. These are dog whistles that willfully ignore the consequences and already marginalized communities that will be hurt.

“They don’t consider the repercussions of child labor—the injury rates, the school dropout rates,” Maki says.

Another twisted justification for allowing child workers is labor shortages, due to factors like long-covid keeping people home sick, covid deaths, and a decline in immigration during the height of the pandemic. Also, the most dangerous jobs are often underpaid, which makes it difficult to attract adult workers, opening the door for exploiting children.

Maki speculates that legislators who support loosening child labor laws do so because they see it as a way to address labor shortages.

“Don’t address labor shortages on the backs of teen workers, especially in dangerous workplaces. Instead, raise wages and hire better-equipped adults,” Maki says.

Agriculture is a dangerous industry—and one that benefits from FLSA exemptions. In agriculture, children as young as 16 can work hazardous jobs like operating a forklift or handling and applying chemicals for over eight hours a day.

The United States Government Accountability Office found in 2018 that more than half of all work-related deaths among children occur in agriculture, though the industry employs less than 6% of all child workers (again, likely an undercount).

“We’re particularly concerned about kids working in tobacco fields because the crop is toxic,” Maki says. “Kids wear black plastic garbage bags while they work in oppressive heat to protect themselves.”

One such kid was Jose Velasquez, who immigrated to the US with his mother from Mexico when he was ten months old. When he was eight, he began working on a blueberry farm and switched to a tobacco field at 13.

“A typical day spanned from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., with an hour for lunch,” Velasquez, now a college sophomore, recalls. “Tobacco is grown in the summer and North Carolina is a humid state. Some couldn’t even eat or keep down lunch because they were so dehydrated and exhausted.”

It wasn’t just physical hardships, either. Velasquez remembers the pain of returning home so exhausted, he didn’t have the energy to play with his friends during the sun-filled summer evenings.

A typical day spanned from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., with an hour for lunch. Tobacco is grown in the summer and North Carolina is a humid state. Some couldn’t even eat or keep down lunch because they were so dehydrated and exhausted.

—Jose Velasquez, who worked as a child harvesting tobacco in North Carolina

Children Face Unfair, Unequal Treatment

It’s no coincidence that in the 1930s when the FLSA was written, and agriculture was exempt from various restrictions, Black people disproportionately worked in agriculture.

In no uncertain terms, Maki states the underpinnings of child labor in agriculture are racism, stemming from slavery and now most prevalent among migrant children. Most migrant children today are Latin American, seeking asylum from countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, he says.

Mary Miller Flowers, director of policy and legislative affairs at The Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights, adds that these children are already coming from the margins of society, fleeing poverty, violence, and climate change displacement.

“Our narratives about teenage Black and brown boys, gang and infiltration language, all of it is coming from a racist perspective on who does and doesn’t belong,” Flowers says.

The number of unaccompanied minors arriving to the US reached a high of 130,000 in 2022. Upon arrival, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) takes responsibility for placing children with sponsors. With many children and pressure to move them quickly out of detention centers, which cannot adequately serve children’s needs, HHS caseworkers were overloaded and may have made mistakes in the vetting process for sponsors, according to a 2023 New York Times investigation.

Once on the farm, Velasquez describes a “power dynamic” that puts undocumented immigrants at further risk.

“Sometimes we worked on small family farms,” he says. “The farmer’s children, most often white, got longer breaks, got to go inside and wait for the day to cool down. We didn’t have those benefits; we were expected to work 11 hours non-stop.”

Instability also contributes to disproportionate risks of child labor exploitation. UNICEF, for example, reported a correlation between a rise in poverty and an increase in child labor.

The COVID lockdown accelerated these conditions. While many families faced tight economic situations, children were resigned to remote learning. This reality made for a perfect storm for child labor as Human Rights Watch reported remote schooling and financial hardship led to more children working.

Low grades and dropout rates are intrinsically tied to how many hours a child works, according to NCL and studies that found children who work over 20 hours a week are more likely to drop out.

The Kids Need Our Help

Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA) reintroduced the Children’s Act for Responsible Employment and Farm Safety of 2022 (CARE Act) before retiring at the end of the last congressional session. Rep. Raul Ruiz (D-CA) recently reintroduced the legislation in June 2023.

The bill proposes several new federal child labor restrictions, including pesticide use and undoing agricultural exemptions. It also imposes new reporting requirements for work-related injuries and deaths of agricultural employees under 18, as well as new and more severe criminal violations and fines.

Maki is a strong advocate for steeper fines.

“The $1.5 million fine PSSI got this time is one day of revenue for them,” he says. “This was not enough of a consequence—all the owners got off scot-free even though they knew the children were there.”

This kind of work can’t be solved overnight, but Maki is committed to it: “Here we are, 80 years later [after the FLSA], and we’re still trying to fix it. At every session [of Congress], [NCL] will support a bill to raise the age that children can work until it passes.”

Don’t address labor shortages on the backs of teen workers, especially in dangerous workplaces. Instead, raise wages and hire better-equipped adults.

—Reid Maki, National Consumers League (NCL)

Systemic change is at the core of the issue, especially for migrant children.

“Family separation means children end up in more vulnerable positions and there’s very little opportunity for them to develop trusted relationships with anyone, let alone someone managing their care,” Flowers says. “The less institutionalization of children the better.”

Community and peer-based support and resources are also key.

“We don’t want the government to regularly check in on these families,” she explains, noting their inherent and understandable distrust of the government. “They should be able to access meaningful services with people they can trust, like a church or peers who have navigated this reality themselves.”

Velasquez wants people to educate themselves on the reality of child labor and make changes in their everyday lives.

“Learn what companies are profiting from child labor and don’t buy their products,” he says, recommending instead to buy Fair Trade certified and avoid meat from large corporations.

You can also contact your representatives and demand support for legislation like the CARE Act and immigration reform, report labor violations to the DOL, vote in shareholder proxy ballots, and choose socially responsible investments.

Make Your Voice Heard!

To take action against child labor, check out the work of these organizations:

• A More Perfect Union: Sign its petition urging governors and state legislators to stop child labor in your state now.

• The Young Center for Immigrant Childrens’ Rights provides support for children who need legal protection from labor exploitation. You can volunteer with them to support children in need of protection.

• The Child Labor Coalition has resources for apps and browser extensions that can help identify, monitor, and report child labor or if your purchases are supporting companies with bad labor policies.