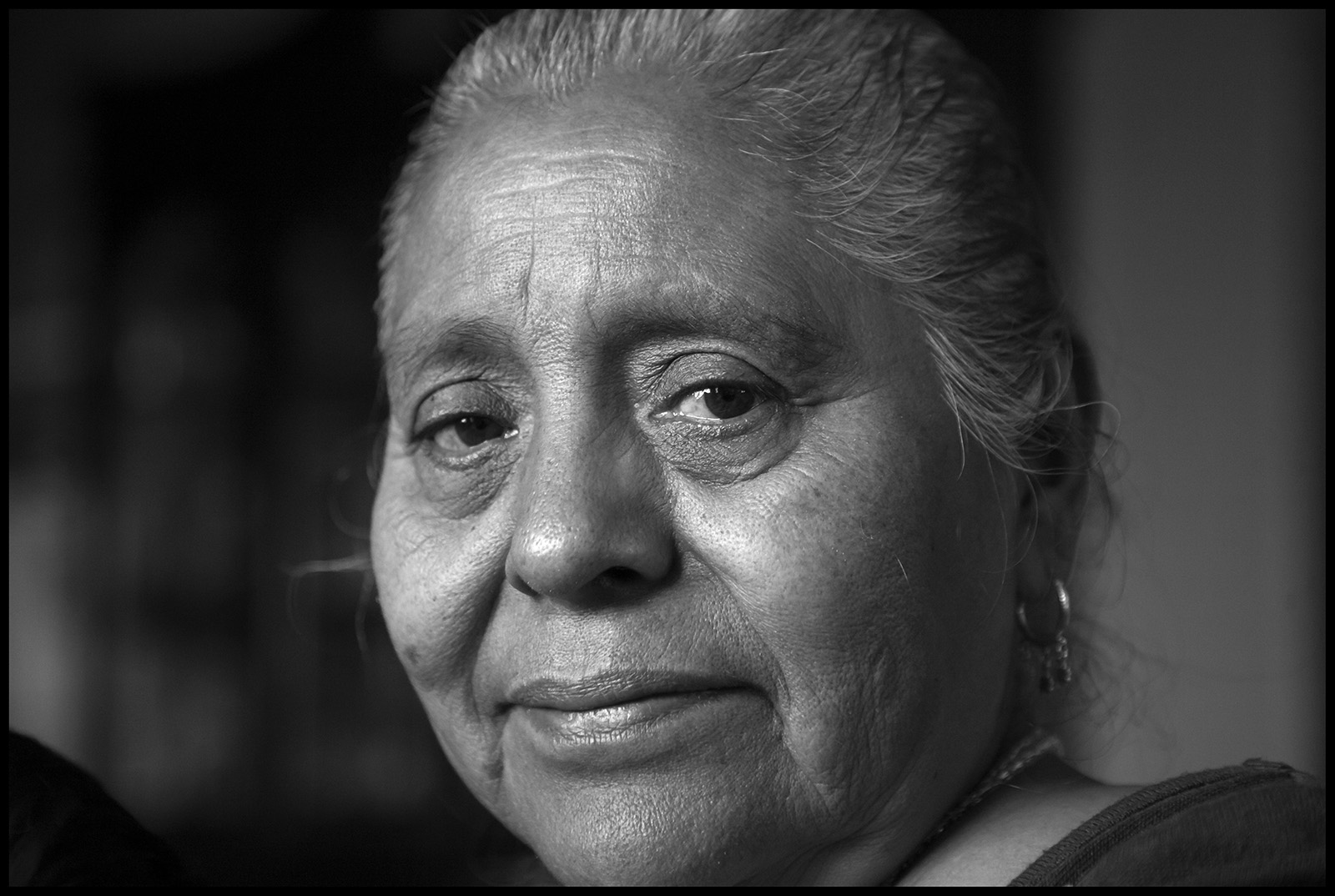

Lucrecia Camacho comes from Oaxaca and speaks Mixteco, one of the Indigenous languages and cultures of Mexico that were hundreds of years old before the arrival of the Spaniards. Today she lives in Oxnard, CA. Because of her age and bad health, she no longer works as a farmworker, but she spent her life in Oxnard’s strawberry fields, and before that, in the cotton fields of northern Mexico.

I’ve always worked the strawberry harvest here in Oxnard. I’d finish that in July and go to Gilroy to work the jalapeño peppers, bell peppers, and cherry tomatoes. I brought my oldest daughter and son with me, and the three of us worked there. They would get out of school in June and worked July and August with me to earn money for their school clothes. They went back to school the 15th of September, so they worked with me 40 days.

I’d take my kids back to Oxnard for school and return to Gilroy to work all of September and October. I lived in a large room that was divided into smaller rooms. It had a stove and outdoor bathroom. We were paid by the piece rate instead of the hour. They paid 80 cents for a bucket of jalapeños—[those] with the stem were paid at $1.10 a bucket. I was able to fill 38 to 40 a day.

I’d get back to Oxnard in November, rest a bit, and then start the strawberry harvest again about January 20th. I worked a long time in Gilroy, starting in 1985. It’s been six to eight years since I haven’t gone. I couldn’t find housing one year, and after that, they wouldn’t hire me anymore.

In strawberries, they also paid by the piece rate in April, May, and June. The other months, they paid by the hour. When I first started, it was three dollars an hour, and the piece rate was 80 cents a box. The year before, I was paid $8.25 an hour. The regular box rate was $1.25, the little box was $1, and the two-pound box was $1.50. If I was able to fill 40 boxes, it was a good day. The younger, faster men can pick 70 to 90 boxes a day.

The strawberry harvest looks easy enough, but once you try it, it’s hard. I don’t wish that kind of work on my worst enemy. When you’re young, you work hard and get tired, but once you get home and take a shower, you’re fine. Now that I’m old, I deal with arthritis and osteoporosis; my feet hurt, and they swell. Many workers have been permanently injured. I have a nephew who hurt his back working in the strawberries, and a cousin who died of pneumonia because we worked in the mud when it’s raining.

The fruit that brings the most money here is the strawberry crop, but they pay us a wage that hardly allows us to make a living, then they turn around and sell each box of strawberries for $18 or $20. If we pick 80 boxes, how much do you think they make from that? You’d think the owners would have enough money to pay workers higher wages, but they pay it to the foreman instead. He has a brand new car every year, and the worker doesn’t get anything.

The foremen now choose workers who can pick 100 to 130 boxes per day. I know one who only hires immigrants without papers because she says legal residents complain too much. They tell the ones without papers they’re going to call immigration officials or fire

them if they complain. These workers try and stay on the foreman’s good side by bringing her homemade tortillas, mole, and even Chinese food. I’m not going to bring her anything. I don’t get paid enough. If the foreman doesn’t like you, he makes you redo the work. In the strawberry fields, you’re always worried that the foreman is going to send you back and tell you to redo your box because it’s not full enough.

We just have to put our heads down and work quietly. There were many times I stayed quiet and didn’t defend a fellow co-worker, but one time I did speak up. I had a woman foreman who spoke to us disrespectfully; when I asked her why, she told me to give her my tools and fired me. I told her I didn’t understand why I was being treated that way, but the other foreman grabbed me by the arm and told me to leave.

Our work and life are hard here, and we don’t see many benefits. Have you seen the current gas prices? Before, we had to work an hour to cover our cost of gas, and now we have to work two hours. We don’t have anything left. The more we earn, the more they take away. We can’t move forward.

I tell my kids how much I’ve struggled. I’m old now, so the last four years, I was told I worked too slowly. But it’s difficult to work in the rain and mud. At times, you’re lucky and find a good foreman who gives you waterproof ponchos. Other places charge for them, $25 for ponchos and $25 for rain boots.

I felt so strong when I was young. I could work 24 hours. When I was picking cotton in Mexico, I could easily lift 50 kilos (120 pounds). I don’t know if it’s old age or my diabetes, but I work a lot slower now. The machine in the strawberry fields goes very fast, and it’s frustrating to get left behind. I can’t fill the amount of boxes I used to. I feel [nauseous] and get headaches.

They won’t give me a job anymore. If the foreman doesn’t like you, then you aren’t hired. They always choose the pretty women and family members first. As a woman working in the fields, if you didn’t have a good foreman, you were treated badly. You had to ask for permission to take a day off, but you were given a ticket. After accumulating three tickets, you were fired.

I’ve also heard complaints of sexual harassment from women. Sometimes, women don’t want to speak up. There are a lot who have

lived through it but are afraid to say something for fear that they’ll be reported to immigration officials.

In Culíacan, when I was young, I had a foreman who always sought out women to be alone with. He said he liked me, but I told him I knew he had a wife and mistress. He told me that if I let him do what he wanted to me, I would still have a job. If not, I needed to look for another one. I told him he would not see me there the next morning. Some of us women don’t take that kind of abuse, but many do what they feel necessary to keep their jobs, even if it means being in the hands of the foreman. My daughter tells me about her factory job and how that still happens there. The women that let the foremen do what they want move up in position. Those that don’t, stay in the same position.

We need someone to help us and provide us with support. There are only a few of us in Líderes Campesinas. [Editor’s note: Lideres Campesinas is a nonprofit organization that develops leadership among women farmworkers, so they serve as agents of political, social, and economic change in the farmworker community.] If I had a hidden camera, it would be so easy to show others what we face. I think a union would help, but it’s been difficult for one to get organized in the Oxnard area. When I began to wear my Líderes Campesinas T-shirt, I was told there wasn’t work for me anymore. I’ve been looking for work ever since.

When I came here, I didn’t expect a better life. I knew I would have to earn my living with physical labor. ... I hope to retire soon and go back to Mexico. I don’t plan on staying here, and I’ll leave neither rich nor poor. The only thing I’ll take with me is aches and pains, because it’s not like I have any money to take with me.